Naïve Bayes

Requirements

- Deep understanding of Bayes’ rule

- Machine Learning fundamentals (Maximum Likelihood Estimation, what inference, training mean)

Problem

One of the common tasks in natural language processing is the classification of some specific text. We may want to see if it’s spam or anti-spam, if it reflects positive or negative sentiments, if the author is male or female, and so forth. Before the actual classification task though, some processing on the text is required in order to ease the classification task (we cannot just feed the data as-is into the model). We will kick off with this task in the first paragraph and then we will extend the context with the actual classification reasoning.

Assumptions

Caveat

In NLP, we commonly refer to a text (which can contain a review, a novel, an email) as a document. A collection of documents forms a dataset.

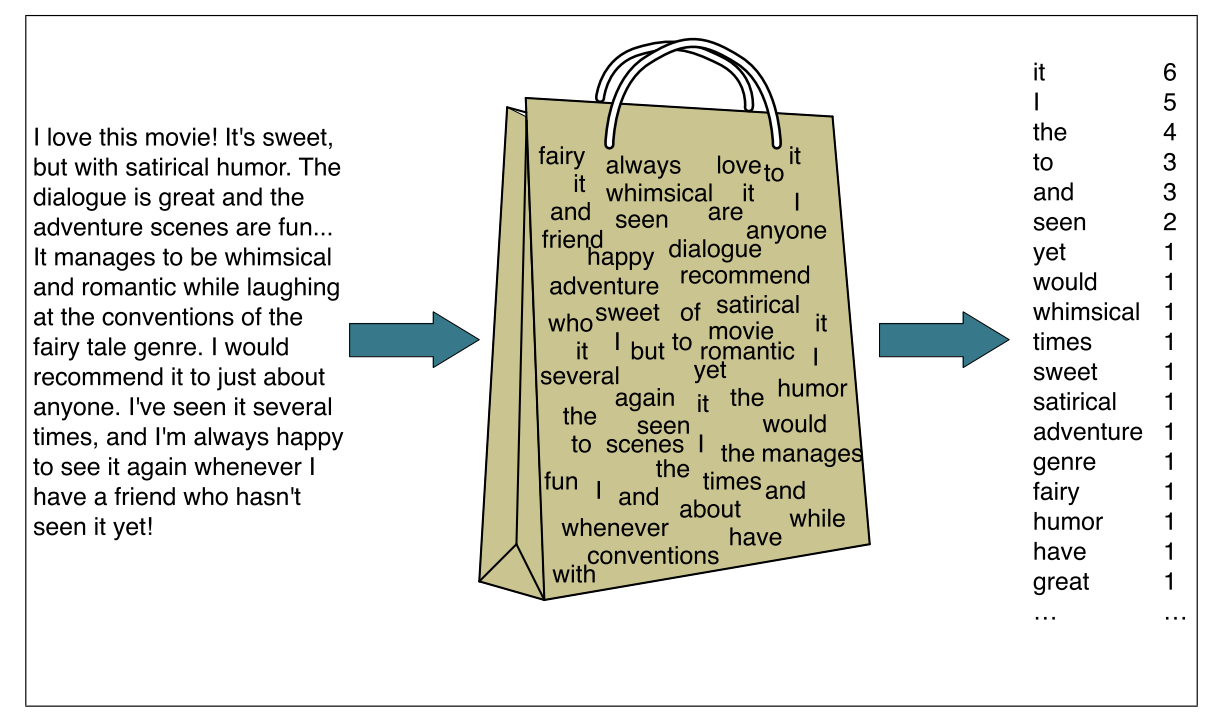

Bag-of-words

In order to use a Machine Learning model, one should obtain some features based on the respective text. What kind of features can one get? One intuitive way is to assume as features the frequency of the words present in the text. If word ‘fabulous’ is used 2 times in the text, one could think that the text is positive (unless ‘fabulous’ is used sarcastically). Hence, we can collect the numbers of occurrences of each word in the text and use them as features for a document. Therefore, by using this approach, we are discarding the sequential relationship between words in the text. This is commonly called the bag-of-words assumption - we are essentially discarding the sequential information and treat the text like a “bag” of randomly positioned words.

Model

The next thing one should consider is what kind of modeling we can do now. Remember, our main goal is to classify this text (we’ll keep it rather generic in this text and we consider classifications of any type - although, you can think of sentiment analysis as a particular example - we want to predict what sentiment the author had when writing the specific text/review/tweet/etc.). Intuitively, one way to model this problem and to put it into a Machine Learning framework is to assign a probability distribution to the class, given the text:

\[P(positive|text) = some\_prob\] \[P(negative|text) = 1 - some\_prob\]In this framework, we can make predictions about the document (is it positive or negative and how accurate our prediction is ?). Furthermore, the document is just a collection of word features, as we said in the bag-of-words assumption. More specifically, the probabilities from above can be decomposed as follows:

\[P(positive | text) = P(positive | word\_freq_1 , word\_freq_2, ...)\]Now, given this probability distribution, how can we compute it?

Generative and discriminative models

In Machine Learning, there are 2 categories of models that are used for classification tasks:

- generative (models learn the distribution that the data belongs to and can generate data)

- discriminative (models learn a function based on the existent features in order to discriminate between the existing classes)

As usual, there is a trade-off between these 2 types of models.

- Generative models have the advantage of being able to generate data which is useful in various scenarios. The drawback is that they often impose a constraint on the data (the data is Gaussian distributed, or, more generally, distributed according to a predefined distribution). It is for this reason that generative models don’t have too much flexibility when learning a distribution.

- Discriminative models, on the other hand, can be particularly useful for figuring out the underlying mathematical function that maps the features to a specific output (in this case, the class). The drawback is, naturally, the fact that this models cannot generate data, since they just learn a mathematical function, which always needs an input in order to discriminate.

In a nutshell:

| Generative Models | Discriminative Models | |

|---|---|---|

| Flexibility | ||

| Data generation |

Now, for the sake of this problem, we assume that we want to make use of a generative model. Hence, according to the assumptions made by generative models in general, we will characterize our data by providing distributions for each class \(P(c)\) and distributions for \(P(f_i | c)\), where \(f_i\) - one of the features that we’re using (as we saw before, we’re considering as features the occurrences of each of the words within the text - \(f_i=word\_freq_i\)). So, given this distribution, we have essentially 2 goals (generally, in any ML problem):

- Training

- Inference

Training

On this issue, the first question one has in mind is, how can we reduce our probabilities from before (i.e. \(P(positive | text) = P(positive | word\_freq_1 , word\_freq_2, ...)\) ) to a combination of \(P(c)\) and \(P(f_i | c)\), since these last 2 represent how we actually define our generative model. The answer is, as the title of this post suggests, Bayes.

Bayes’ rule

Simply put, we can decompose the probability using Bayes’ rule as follows:

\(P(positive | word\_freq_1 , word\_freq_2, ...) = \frac{P(word\_freq_1 , word\_freq_2, ... | positive) \cdot P(positive)}{P(word\_freq_1 , word\_freq_2, ...)}\)

Does this look familiar? If we have a look at the numerator, we see the similarity between those probabilities and the ones that define our generative model. We need some further processing on the first term - \(P(positive | word\_freq_1, ...)\) - in order to get exactly what we need.

Naïve Bayes

Let us have a look at the numerator from the Bayes’ rule corresponding equation.

We can identify - \(P(positive)\) - from that equation. \(P(positive | word\_freq_1 , ...)\) looks also similar, but not identical. What can we do to make it identical? The answer is the Naïve Bayes assumption. In a nutshell, we assume independence between the features given the class. To realize why it is naïve, let us walk through the following example. Assume we have the next corpus of data:

-

In my opinion, the movie is not so bad. - positive

-

In my opinion, the movie is bad. - negative

-

In my opinion, the movie is quite bad. - negative

If we consider the word bad and we compute the probability of its existence given the class, we would intuitively get: \(P(bad|positive) = \frac{1}{3}\). However, if we consider the other features as well, we get a larger probability, i.e. \(P(bad|positive, not, so) = 1\), which is essentially 100% chance of having the word bad in our document, since we have only such an example. So, as we can see, bad can have positive connotations given other features from the text. That’s the main reason why the assumption that \(P(bad|positive, not, so) = P(bad|positive)\) is called naïve.

Inference

Moving forward, we now have almost all the ingredients to predict the class of a certain document. Let us examine the Bayes’ rule equation to understand what is missing. After considering the naïve assumption, what we end up with is: \(P(positive | word\_freq_1 , word\_freq_2, ...) = \frac{P(word\_freq_1 | positive) \cdot P( word\_freq_2|positive) \cdot ... \cdot P(positive)}{P(word\_freq_1 , word\_freq_2, ...)}\)

Essentially, at this point, assume we have learned the prior \(P(positive)\) and the probabilities of the features \(P(word\_freq|class)\) that characterize our generative model. What we still need in order to predict the class of the text is the denominator from the equation from above \(P(word\_freq1, word\_freq2, ...)\). Since this is not normally easy to compute (we have to consider all possible combinations of all the features), we can simply drop it and consider only the numerator for the classification of the text. The consequence is that we do not have a probability distribution anymore (since we drop the denominator, which acts as a normalizing term), but the proportionality still holds, thus giving us the more likely class with the higher score.

Training

Up until now, we have seen how to actually use our model to predict the class of a certain text. The way this normally works, as in any Machine Learning setup, we first obtain these probabilities via training and then try to perform inference. In order to obtain these probabilities, we need to get the parameters of the corresponding distributions, by using the training data in order to estimate them. For getting the right parameters, we can use various approaches, among which Maximum Likelihood Estimation, Maximum a Posteriori, or full Bayesian approaches by estimating the full posterior are all suitable choices.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: